Chaucer's Canterbury, Emily Brontë's moors, Graham Greene's Brighton, Kureishi's suburbia … The British Library's new exhibition explores how literature has responded to the varying landscapes of these islands.

|

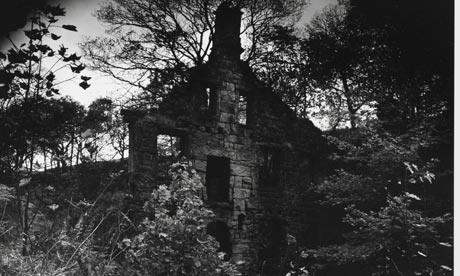

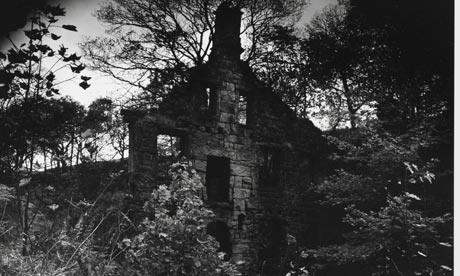

| for Ted Hughes's Remains of Elmet. Photograph: Fay Godwin |

Can Britlit be said to exist? Britart is an accepted term, and Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Gillian Wearing et al were happy to be known as YBAs, if only for the publicity it brought them. But YBWs? Or OBWs? Or even M-ABWs? They're harder to imagine. Writers living in northern and western parts of our archipelago identify themselves as Scottish or Welsh (or Cornish), not British. The term is also unacceptable to Catholics in or from Northern Ireland: "British, no, the name's not right," Seamus Heaney politely demurred, when Andrew Motion and I included him in The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry 30 years ago. Most English writers, meanwhile, use the word British at best half-heartedly: it sounds inclusive – free of master-race arrogance, antagonism towards Celts or National Front jingoism – but it doesn't describe what we think we are or where we come from....

The British invariably perceive the countryside as being under threat, whether from bombs, developers, tourism, climate change or the passage of time. This makes our literature nostalgic – a land of lost content. There are legends of Arcadian plenitude – of Albion, Mercia, Elmet; of life under the greenwood tree, or in the highlands before the clearances, or in green valleys before the coming of industry...The gods of the earth seem to be extinct but then pop up again, rudely healthy and full of folk wisdom. Anglo-Welsh poet Edward Thomas meets one such man at hawthorn time in Wiltshire and is told his many different names:

The man you saw – Lob-lie-by-the-fire, Jack Cade,

Jack Smith, Jack Moon, poor Jack of every trade,

Young Jack, or old Jack, or Jack What-d'ye-call,

Jack-in-the-hedge, or Robin-run-by-the-wall,

Robin Hood, Ragged Robin, lazy Bob,

One of the lords of No Man's Land, good Lob, –

Although he was seen dying at Waterloo,

Hastings, Agincourt, and Sedgemoor too,

Lives yet. He never will admit he is deadHe still won't admit it: in his latest incarnation he appears as the charismatic Johnny (Rooster) Byron in Jez Butterworth's play Jerusalem...[another] likeable and perhaps defining aspect of Britishness is a capacity to find poetry in unlikely places.

Read the rest of Writing Britain: the nation and the landscape | Books | The Guardian

More:

- Guardian Books podcast: Writers and the British landscape: As the British Library exhibition Writing Britain opens, curators Jamie Andrews and Tanya Kirk guide us through the imaginative territories writers have carved out from these British Isles

Locating the books with the strongest sense of place

No comments:

Post a Comment